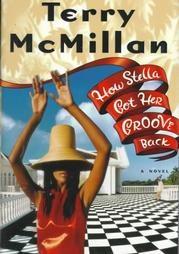

It was a book. It was a movie. But most of all, it was a phenomenon of modern femininity. The quintessential feminist anthem: Those oppressive Men commit deadly sins, and engage in predictably self-destructive, exploitive, morally reprehensible behavior.

Us too, sister. You go, girl! Up the Revolution!!

And what was more; and what was better – what made it so real, so genuine, so

Charlie Rose – was the not-so-incidental fact that (as only cave-resident readers knew not) Terry McMillan was not merely the author of “

How Stella Got Her Groove Back,” but she had walked that walk, had danced to that tune, and had glowingly buffed up her very own groove with a studly young fella of an age to be her son. And brought him home, to boot.

I am woman. My mystique is no mistake. No second sex for me. At last, a room of my own.

The novel was not complex.

Publisher’s Weekly synopsized:

Her "forty-fucking-two-year-old" heroine, divorcee Stella Payne, possesses a luxurious house and pool in northern California, a lucrative job as a security analyst, a BMW and a truck, a personal trainer and an adorable 11-year- old son-but no steady guy. On a whim, Stella decides to vacation in Jamaica, and she narrates the ensuing events in a revved-up voice, naked of punctuation, that alternates between high-voltage energy and erotic languor. Romance comes to Stella under tropical skies-but there's a problem. Gorgeous, seductive Winston, the chef-trainee with whom she enjoys passionate sex (explicitly detailed), is shockingly young: he's not quite 21. Naturally, Stella wonders if he really loves her; endless soul-searching and a few tepid complications occupy the remainder of the narrative. When Stella loses her job, it's no sweat; she has enough savings to maintain her lifestyle. When fate throws two other gorgeous men her way, she immediately decides they are boring and isn't tempted for a minute.

The Washington Post said (5/5/96):

She revels and even gloats at being a woman, revels in being in solitary possession of her mind, her body, her child, her house, her finances, her beauty, her creativity and finally, of her sexy, strapping young dream lover, whom she finds and triumphantly lashes to her side. If this is unserious literature, it is unserious literature of the most serious kind, perhaps even, in its own way, revolutionary.

Indeed, the

Post’s reviewer girlishly gushed:

Terry McMillan is the only novelist I have ever read . . . who makes me glad to be a woman.

The New York Times Book Review explained (6/2/96):

. . . [A] guilty-pleasure sex-and-shopping fantasy of the first order, sprinkled with asides on rap music and feminine hygiene and featuring a message as uncomplicated as a glass of fresh-squeezed papaya juice: If aging men can rev their engines with pretty young trophy wives, why can't middle-aged women treat themselves to dreamy, dishy boy toys?

Why not, indeed?

Perhaps because reality has a tactless predisposition eventually to assert itself. That butter-skinned trophy wife, that Ferrari in the bedroom (with

Body by [Dr.] Fisher), rather quickly evolves into the narrow-eyed time-server, filing her nails and your bonds against the day of her liberation. Just how long will she defer her pay-day?

And so, apparently, has it turned out not for Stella, but for her creator, Terry McMillan. You could read the story in the

WaPo today, but for this purpose it must be agreed that reference to the

San Francisco Chronicle is more apt:

In a tale rich in lost love, closeted secrets and acrimonious divorce, it turns out that famed local writer Terry McMillan -- whose celebrated romance and subsequent marriage to a man 23 years her junior became the subject of her fictionized best-seller "How Stella Got Her Groove Back" -- actually got her groove back with a man who now says he's gay.

Not, of course, that there’s anything wrong with that. Terry explains further:

In court papers . . . McMillan leaves little doubt that she believes Plummer [her boy toy] was always motivated by money.

"Jonathan has manipulated me from the very beginning in his scheme to come to the United States, become a citizen and get rich through someone else's effort,'' McMillan wrote in one of her filings.

In fact, McMillan says Plummer zeroed in on her precisely because of her celebrity status as an author whose earlier books included "Waiting to Exhale, '' which sold some 4 million copies and was made into a movie.

In an interview, Plummer insisted that he didn't know he was gay when he met McMillan in June 1995 at a Jamaican resort. Nor, he says, did he seize on the author's fame.

No fool she, there had been a little voice:

For her part, McMillan, who was then 42, said she worried when she first met Plummer that he was interested only in her money. "But Jonathan was very charming and made me believe that he was crazy about me,'' she told the court.

A voice ignored, alas:

The two eventually married in Maui on Sept. 8, 1998 -- but not before Plummer signed a prenup that waived his rights to everything should they ever part, including "temporary and permanent spousal support and attorney's fees, '' according to court papers filed by McMillan.

The couple settled in McMillan's $4 million Danville home and, at least according to Plummer, enjoyed a happy life -- until the last few years when the marriage started coming undone.

"He became less attentive, less charming, more distracted and absent from the home,'' McMillan wrote in her declaration.

Plummer said he was spending long hours with a dog-grooming business in Danville that McMillan had set up for him a couple of years ago in apparent anticipation of a split.

Dog grooming. Less attentive. Less charming. More distracted. A story as old as mankind. But what precipitated the revelation? In the age of Oprah and Dr. Phil, you already know. A one-on-one intervention:

McMillan says Plummer confessed to being gay only after she confronted him about all his hours of phone calls to a male friend living in Jamaica. She also says she later learned that Plummer was participating in online gay chat sites.

If only mommy had been wise enough to set up those parental controls, all of this might have been avoided.

But there is an instructive postscript. McMillan appeared

last evening near Washington, D.C., to promote a new book. When question and answer time came, she warned the crowd:

"Not nary a question about my marriage, or my divorce, or homosexuality, or I will ig nore you," McMillan instructs, shaking a finger.

Ponder that for a moment. What, precisely, does she mean? That her private life is private? That she is embarrassed?

But mattress gymnastics with her beamish boy was hailed by the

New York Times, acclaimed by modern thinkers, and provided a not inconsiderable contribution to an impressive personal fortune. No signs then of modesty.

Has she, perhaps, actually learned something? We may pray that she has.

In the meantime Ms. McMillan may now, we presume, apply for re-grooving.